Developers turned farms into planned communities

Bay Farm Island was a farming community long before its first residential neighborhood of homes grew along Garden Road from the 1920s to the 1940s. Homes first crept onto the Uplands in the late 1940s, introducing the ABC drives—Azalea, Begonia, and Camelia—among other streets. By the early 1960s, developers were busy creating homes on the southeastern end of the Uplands, where Magnolia Drive, Lilac Street, and Oleander Avenue embraced the cul-de-sac they created at the end of Fitchburg Street.

In the mid-1960s, the first major developer had taken an interest in developing the Uplands. Robert Braddock and R. H. Logan had formed the Braddock & Logan construction company in 1947. They approached farming families along Mecartney Road, west of the two neighborhoods already on the Uplands, and offered to buy their properties. Enough of the families agreed to sell, so the partners approached the City and got permission to develop their newly acquired real estate.

Join Alameda Post historian Dennis Evanosky as he concludes his three-part walking tour of Bay Farm Island. He will give participants a first-hand look at how Bay Farm developed from a farming community to neighborhoods of homes. Meet at 10 a.m., Saturday, May 6 or Sunday, May 14 at the Bay Farm Library, 3321 Mecartney Rd. for a leisurely two-bridge stroll through Harbor Bay Isle and let Dennis share the story of how all of Bay Farm Island developed. Advance tickets are $20, and a limited number may be available for sale at the start of each tour. More tour info.

Braddock & Logan turned the first spade of earth there in 1966. Within three years, they had created the townhome village of Casitas. In 1969, they acquired and developed more farmland. By 1971, they had created 438 townhomes there and named this second neighborhood “Islandia.” Sales of the townhomes were brisk. The developers then began building their third neighborhood, Garden Isle.

Utah Construction arrives

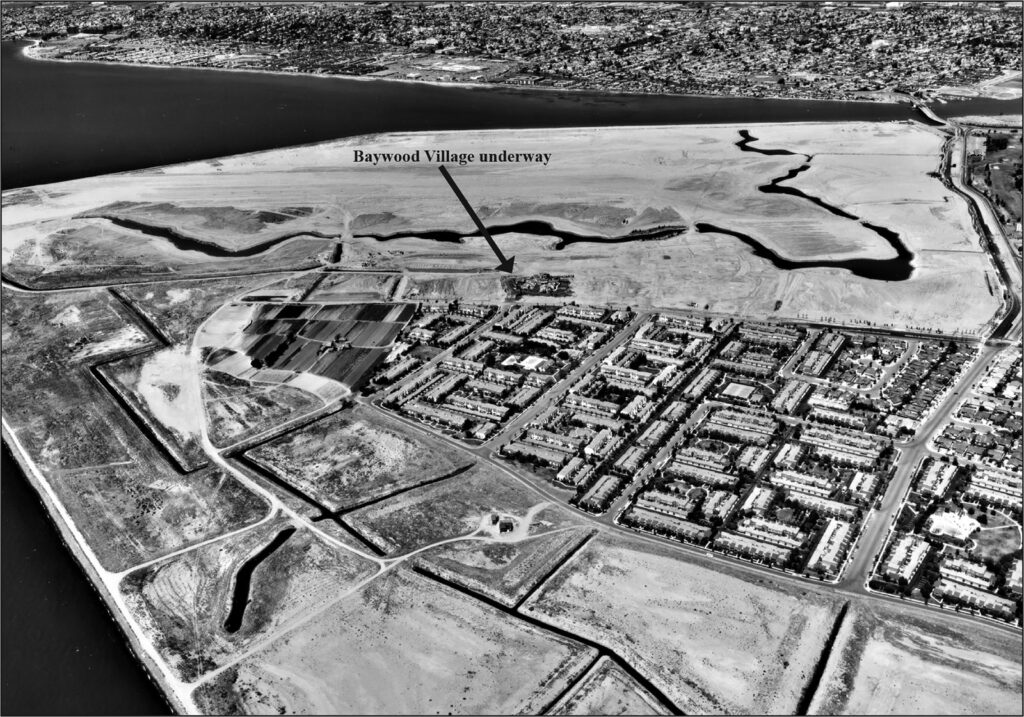

The same year Casitas was rising from the soil of the Uplands, Utah Construction arrived to define the boundaries of the tidelands they had acquired over time. By the time Braddock & Logan had begun construction on Islandia, Utah’s dredge, the Franciscan, had created land where there was once water and marsh. This set the stage for a new development, much larger than most even imagined.

In 1972, Utah teamed up with Ron Cowan’s Doric Development, Inc. to form Harbor Bay Isle Associates. Together they created a master plan to build 10,000 homes on the landfill property that Utah Construction had shaped on three sides of the Uplands, where Braddock & Logan was busy with its developments. Doric and Utah divided Harbor Bay Isle into five villages, which today encompass 20 homeowners’ associations. They planned part of Village 1 to include a synagogue, a church, the library, a park and the Harbor Bay Club. They set aside adjoining property for a shopping center.

First Braddock & Logan and now Harbor Bay Isle! Alamedans cast a very nervous eye on what was going on, especially on all the landfill that Utah Construction had created. Not another South Shore, they objected. Smaller developers were also purchasing farmland to develop the Uplands. And all those apartments and condos on South Shore? Concerned Alamedans did not approve. The developers had even named one of the streets there for that horrid dredge, the Franciscan, islanders protested. This had to stop.

Committee of Concerned Citizens and Measure A

“The quiet residential quality of Alameda (will rapidly disappear) if the construction of townhomes, condominiums, and apartment complexes is allowed to continue,” the Committee of Concerned Citizens declared. “Alameda will be facing a massive tax increase to pay for public services.”

The Concerned Citizens also feared the “Southern Crossing,” a new bridge the state would anchor on Bay Farm Island to carry vehicles across San Francisco Bay to Army Street (now Cesar Chavez Street). Nervous residents also looked askance at the offshore freeway that would run along the South Shore, which they already hated, to the Southern Crossing bridge. The rumor mill spewed out grist about yet another tube. The Webster Street Tube had opened in 1963. Not another one, they protested! Something had to be done.

The Concerned Citizens succeeded in getting Measure A on the ballot, and on March 13, 1973, Alameda voters approved, thus creating Section 26 in the City Ordinances:

Sec. 26-1. There shall be no multiple dwelling units built in the City of Alameda.

Sec. 26-2. Exception being the Alameda Housing Authority replacement of existing low-cost housing and the proposed Senior Citizens low-cost housing complex, pursuant to Article XXV Charter of the City of Alameda.

The measure limited housing density throughout the city and reduced the number of homes that could be built on Harbor Bay from Utah and Doric’s planned 10,000 to about 3,000. The ordinance failed to define “multiple units,” but at its March 27, 1973, meeting the lame-duck City Council added Sec. 26-3, which defined multiple units as “three or more.” At last, Mayberry was safe from those ne’er-do-well developers. The Concerned Citizens now took direct aim at developer Braddock & Logan’s three developments on Bay Farm’s Uplands. The move misfired.

Defining multiple units

On April 17, 1973, newly elected Vice Mayor Chuck Corica and Councilmembers Lloyd Hurwitz and George Beckham took their seats. The Concerned Citizens had helped seat these newcomers and they expected the tyros to do their bidding. Corica, Hurwitz, and Beckham had scarcely warmed their new seats when one of the Concerned Citizens’ leaders, Inez Kapellas, stepped up to the microphone.

She insisted that the City Council vote to include townhomes in the multiple-unit definition, thus prohibiting their construction. She did not mention the two neighborhoods of townhomes that Braddock & Logan had already built on Bay Farm Island’s Uplands: Casitas and Islandia, nor the one they were preparing to build, Garden Isle. She did not have to. In theory, everyone knew that Ron Cowan and his friends had drawn up plans that could turn Mayberry into Gotham City.

After listening to Kapellas, the new Vice Mayor leaned over to his microphone. “I would like to include townhomes in the definition of multiple dwelling units,” the Alameda Times-Star quoted him as saying. Corica was making a motion. This required the City Council to follow proper procedure. That mandated a second and a vote by the full Council. No one spoke up. The silence was deafening as two other members of the “Concerned Citizens” triumvirate, Hurwitz and Beckham, sat taciturn. The motion failed, and with it “Concerned Citizens’” bid to stop the Bay Farm townhomes from being built. The first chink in the Measure A armor had appeared. More would follow.

The lack of support for Corica meant that the Council took City Attorney Fred Cunningham’s advice seriously. As City Attorney, one of Cunningham’s jobs was to prevent any parties from suing the City. He had advised the Council that, unlike apartments, townhomes are considered single-family dwellings with their own tax- and parcel-identification numbers. Even though they may be attached to other townhomes, they are owned—and taxed—separately.

Unlike apartment dwellers, owners of townhomes pay property taxes. Hurwitz and Beckham took Cunningham’s advice. Their failure to follow the vice-mayor’s lead likely prevented not only Braddock & Logan from suing the city but stopped Alameda’s townhome owners from claiming that they do not owe property taxes. The City Attorney had done his job.

Harbor Bay Isle rises

In 1976, three years after all the drama on the Uplands, Doric Development rolled up its sleeves and began building out its 920-acre creation. Doric started with the Harbor Bay Isle Landing Shopping Center. Safeway and Longs moved in as anchor tenants. The first Harbor Bay Isle housing community of 239 attached townhomes began development in 1978. Casitas’ townhome dwellers who lived across Mecartney Drive discovered flyers on their doorsteps about Harbor Bay Isle. The flyer invited them to an auction for 30 yet-to-be-built houses.

Doric’s creation slowly blossomed. Students began attending Amelia Earhart School in 1979. Neighbors started enjoying exercising and swimming at the Harbor Bay Club the following year. Bay Farm Elementary School began classes in the fall of 1991. By then, Fire Station No. 4 had moved from the makeshift station on the grounds of the old drill tower on Island Drive and Clubhouse Memorial Road to a brand-new home at Aughinbaugh Way and Mecartney Road.

In March 1992, the San Francisco Bay Ferry service began carrying passengers between the Harbor Bay Ferry Terminal and the San Francisco Ferry Building. The Harbor Bay Business Park opened in 1994, with the Oakland Raiders as one of its first tenants.

As their neighbors settled in on the Uplands, Doric Development fought to build all the homes they negotiated for in the 1970s. Doric could show that the City owed the company approximately 200 more units. In 2007, the Planning Board nixed “Village VI”—a proposal to build 104 of these homes on a parcel near Peet’s Coffee. Peets told Doric that they had chosen their location because it was far away from any residential areas. Critics of Village VI said that Peet’s would leave Alameda if Doric built any homes there.

Doric lost two more bids to build these homes—Ron Cowan attempted to take the Mif Albright Golf Course away from the city’s youngsters in 2011, but that idea went nowhere. And even today, the idea that Doric will build some, if not all of these homes on the Harbor Bay Club property awakens the rumormongers.

Bay Farm has come a long way, for better or worse, from the days it served our fowl friends as a rookery to the time that the soil offered up a basket of plenty to the residential haven of today.

A heartfelt thanks to Leslie Mladnich for her informative three-part series about Bay Farm Island that appeared in Alameda Patch.

Dennis Evanosky is the award-winning Historian of the Alameda Post. Reach him at [email protected]. His writing is collected at AlamedaPost.com/Dennis-Evanosky.