1630 Lincoln Avenue and 1240 St. Charles Street

When I began looking into a handsome old house in my neighborhood—1630 Lincoln Avenue—I had no idea it would lead to such an interesting story. Not only was the house once owned by Daniel Bruton, an Irish immigrant and prominent local businessman, but his three daughters became known as the “famous Bruton sisters” for their influence on the art world in the 1920s, 1930s, and beyond. In addition, the next house that the Bruton family built—1240 St. Charles Street—is so significant architecturally and historically, that it became an Alameda Historic Monument in 2011. As is often the case, once I crack open the door on a house’s history, what appears out of the darkness is more than I could have imagined.

[1]

[1]Pioneer homeowners on St. Charles Street

In Part 1 [2] of this story, we learned about Daniel Bruton marrying Helen Bell in 1893, when he was 54 and she was 27. After three years of living together on Lincoln Avenue with other family members—including Daniel’s older brother Thomas—the Brutons purchased land on St. Charles Street for a house of their own in 1897. This land was in the Strybing tract, a pristine and undeveloped block of oak trees leading down to San Francisco Bay, which was being subdivided for the first time. By this point in his career, 58-year-old tobacco merchant Daniel Bruton could afford to purchase a prime piece of land close to the bay shore and commission the oldest homebuilding firm in the city, Denis Straub & Son, to create his family’s dream home. The Brutons were among a number of successful business people who bought land on St. Charles Street during this time and built some of the finest homes in the city. The Bruton house at 1240 St. Charles Street was the first in the tract.

Pioneer builders on St. Charles Street

One of the pioneer home builders in Alameda was Denis Straub [3] (1822-1899), a German immigrant who had settled in Alameda by 1866. He later took on his stepson, Fred P. Fischer [4] (1862-1951), who started out as an apprentice and worked his way up to partner, supervising construction and overseeing design. It was Fred Fischer who designed 1240 St. Charles Street, a grand home in the Colonial Revival Style, with transitional Queen Anne elements. The home cost the Brutons $4,160, which was a fair amount in those days, though not nearly as much as some of the other mansions of that era. For example, the mansion that Joseph Leonard built for himself at 891 Union Street [5] in 1896 cost an astounding $20,000 at a time when most homes cost under $4,000.

[6]

[6]Construction started in the spring, shortly after the land was purchased, and the house was completed in about six months. An announcement in the Alameda Daily Argus, dated November 17, 1897, reported that “Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Bruton of Railroad Avenue (today’s Lincoln Avenue) moved into their new residence near the foot of St. Charles Street.” At that point, the Brutons were a family of four, with two daughters having been born while they lived on Lincoln Avenue–Margaret in 1894 and Esther in 1896. Helen was born in 1898, bringing the family size up to five, which the 4,000-square-foot home with two spacious floors–and a large rambling attic and basement–could easily accommodate.

A budding interest in art

As the girls grew up and attended Alameda public schools, their interest in art grew as well. They would often paint and sketch together in the large attic of their new home on St. Charles Street, and all three sisters ended up attending the Art Students’ League in New York after graduating high school. As their education and experience in art evolved, they each developed specialties—Margaret specialized in oil paintings and fresco art; Esther worked mainly in etchings, wood block prints, decorative screens and murals; and Helen devoted her time to mosaic tile murals. At the same time, they were flexible enough to collaborate on projects and work together in whatever medium the job called for. In a 1932 newspaper article, Helen is quoted as saying, “While each of us has her own type of work, we find it a simple matter to work together on many of our problems.”

[7]

[7]The Bruton sisters—world travelers

In 1925 the three sisters traveled to Europe to study art in England, France, and Italy. Margaret stayed on for a year to study at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris. In 1926, when she returned home, she had her first solo show at the Beaux Arts Gallery in San Francisco. She and her sisters became active in many arts organizations, including the San Francisco Society of Women Artists.

Helen first studied sculpture, but later turned to printmaking and then mosaics, including making her own tiles. In 1929, she traveled to Los Angeles, where she was hired to design a series of large scale portraits of famous philosophers to be done in terra cotta tile. That series of 22 philosopher portraits, along with a quote from each, was to be installed in the library of the newly constructed Mudd Hall of Philosophy. The works are still on view today, though they have only recently been properly credited to Helen Bruton, after her contribution was somehow forgotten over the years.

[9]

[9]Esther became an illustrator for the Lord & Taylor department store in New York, and later returned to California and worked for I. Magnin as a fashion illustrator. In 1941, Esther married civil engineer Carl Gilman. She was the only sister to marry, and none of the sisters had children. In 1933, Esther took the lead as the sisters created a dazzling mural in the first bar to open after prohibition, the Cirque Room at San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel.

These projects are just a few examples among many commissions the Bruton sisters took on, not only in the Bay Area but also in Los Angeles and as far away as the Philippines.

The Monterey years

In 1924 the Bruton family had an adobe house built on Cass Street in Monterey, which they used as a vacation home. The beauty of the area enchanted the Bruton sisters, and inspired their art. See Part 1 [2] to view Margaret’s oil painting, Barns on Cass Street, painted in 1925. Helen and Margaret would move there permanently in 1944, and sell the St. Charles Street house after 47 years of Bruton family ownership. Evidence of how much the Brutons loved the Monterey peninsula was found in a March 21, 1906 announcement in the Alameda Daily Argus that said, “Daniel Bruton and family have located at Pacific Grove for the season. E. J. Burns and H. R. Cooper of San Francisco have leased the residence of Daniel Bruton, 1240 St. Charles Street.” They must have fallen in love with the Monterey peninsula during these early stays, leading them to later build a home of their own on Cass Street.

[11]

[11]The Bruton sisters’ big role in the Fair

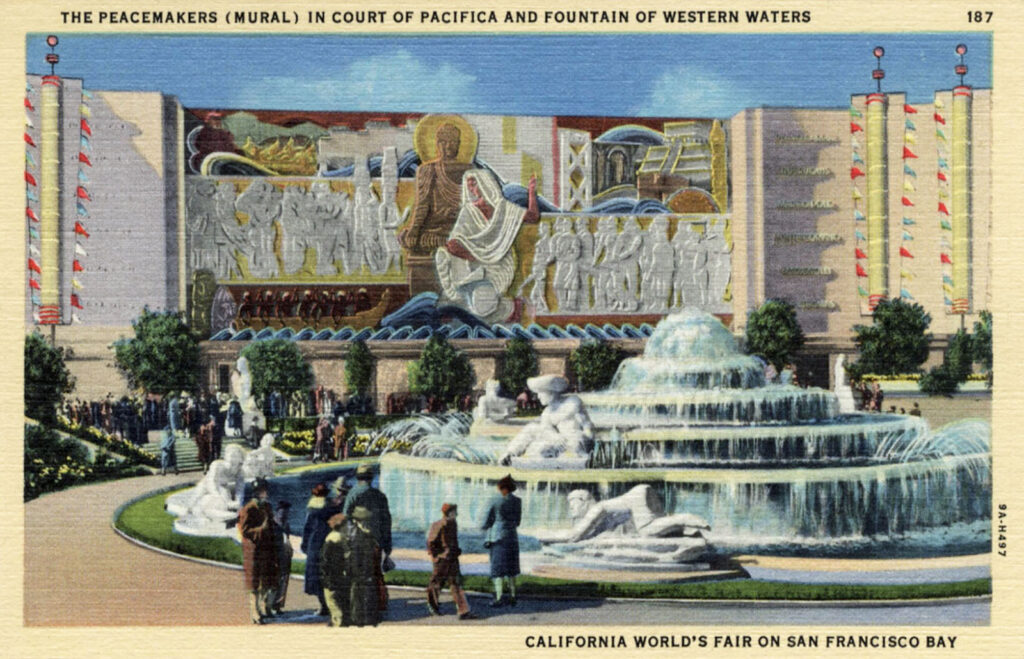

In 1939, the Golden Gate International Exposition opened on Treasure Island, in the middle of San Francisco Bay. The two-season fair was held to celebrate, among other things, the opening of both the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Timothy Pflueger, a well-known San Francisco architect, was one of the organizers of the fair, and was familiar with the work of the Bruton sisters. He asked them to produce the largest mural at the exposition, on a scale larger than anything the trio had ever taken on before. The piece was to grace the west walls of the Court of Pacifica, and the size would be a gargantuan 144 feet long by 57 feet high. Set in place 16 feet from the ground, it would rise to a height of 73 feet.

[12]

[12]The piece was so large that the sisters were unable to use their large attic studio on St. Charles Street to construct the 270 individual 4-by-8-foot panels that would make up the mural, and had to rent space at a furniture warehouse in Oakland for nine months. For anyone who has ever grappled with a standard size 4-by-8-foot sheet of plywood or drywall, try to imagine a project comprising 270 hand-carved and painted panels of that size, all having to come together into one seamless whole.

The mural was done in bas-relief and involved many hours of manual labor carving into Masonite boards, as the sisters worked eight-hour days, six days a week, for nine months. Other prominent artists hired to create murals for the fair included Diego Rivera, Maynard Dixon, and Ralph Stackpole, just to give a sense of how highly regarded the Bruton sisters were in the art world at the time. They received a commission of $20,000 for the project—a very large amount in those days—although much of it went for materials and overhead, and of course to pay the three women for nine months of working full-time. Still, that amount is equivalent to over $430,000 in today’s dollars, and was a big job for the sisters, perhaps the largest single project of their careers.

This part of the story connects to another one of my house histories, the story of 2242 San Antonio Avenue, Part 11 [13]. In that story, current long-time owner Gretchen Lipow attended school on Treasure Island in 1938 and 1939 as her artist father David Kittredge worked on Diego Rivera’s mural, Pan American Unity at the fair. So, one of our previously covered Alameda Treasures, Gretchen Lipow, was there at that same moment in history alongside our current Alameda Treasures [14], the Bruton sisters. I love when connections are discovered between our stories.

[15]

[15]Gone but not forgotten

The only sad note regarding the Peacemakers mural is that it wasn’t designed to be saved after the exposition. Unlike Diego Rivera’s Pan American Unity mural, which was made on steel-framed cement panels that allowed it to be removed and put on display elsewhere after the fair, the Bruton sisters’ mural was not designed to be removed and saved. When the exposition ended after two years, the Bruton sisters were asked if they wanted the mural. Since they had no place to put it, and because removing it would probably have caused significant damage, they allowed it to be destroyed. Helen Bruton was quoted as saying, “I don’t think it’s too bad that those things aren’t saved. They’re made for a certain purpose, and they get a little sad looking afterward.” Toward the end of her life, though, Helen must have been feeling a little more sentimental when she said, “What a pity it couldn’t stay up.”

Next up

As World War II comes to an end and artistic sensibilities change from modernism to abstract expressionism, we’ll see how the Bruton sisters navigate this new world and evolve in their careers. And we may even learn a bit about their grand home at 1240 St. Charles Street, something we haven’t explored in detail because the Bruton sisters themselves are just too darn interesting. As is often the case, my interest starts out with a house, but it’s the people associated with the house that end up being the real story.

For more information on and photographs of Alameda’s famous Bruton sisters and their art, visit Wendy Van Wyck Good’s blog, THE BRUTON SISTERS, Sisters in Art: Margaret, Esther, and Helen Bruton [16].

Contributing writer Steve Gorman has been a resident of Alameda since 2000, when he fell in love with the history and architecture of this unique town. Contact him via [email protected] [17]. His writing is collected at AlamedaPost.com/Steve-Gorman [18].