A curse, a failed land grab, and a murder played roles in bringing the transcontinental railroad West.

On Sept. 6, 1869, a train with Leland Stanford aboard rolled into what would become the City of Alameda three years later. Aboard that train sat one of the Central Pacific Railroad’s “associates.” We remember these men — Stanford, Charles Crocker, Collis Huntington and Mark Hopkins — better as the “Big Four.”

Alfred A. Cohen rode along with Stanford. The state fair was in full swing in Sacramento that day. Cohen and Stanford hoped to entice fairgoers from San Francisco and Oakland to ride the train, instead of the ferry, to the state capital. They paid for advertisements in San Francisco, Oakland and Sacramento’s newspapers advertising their idea.

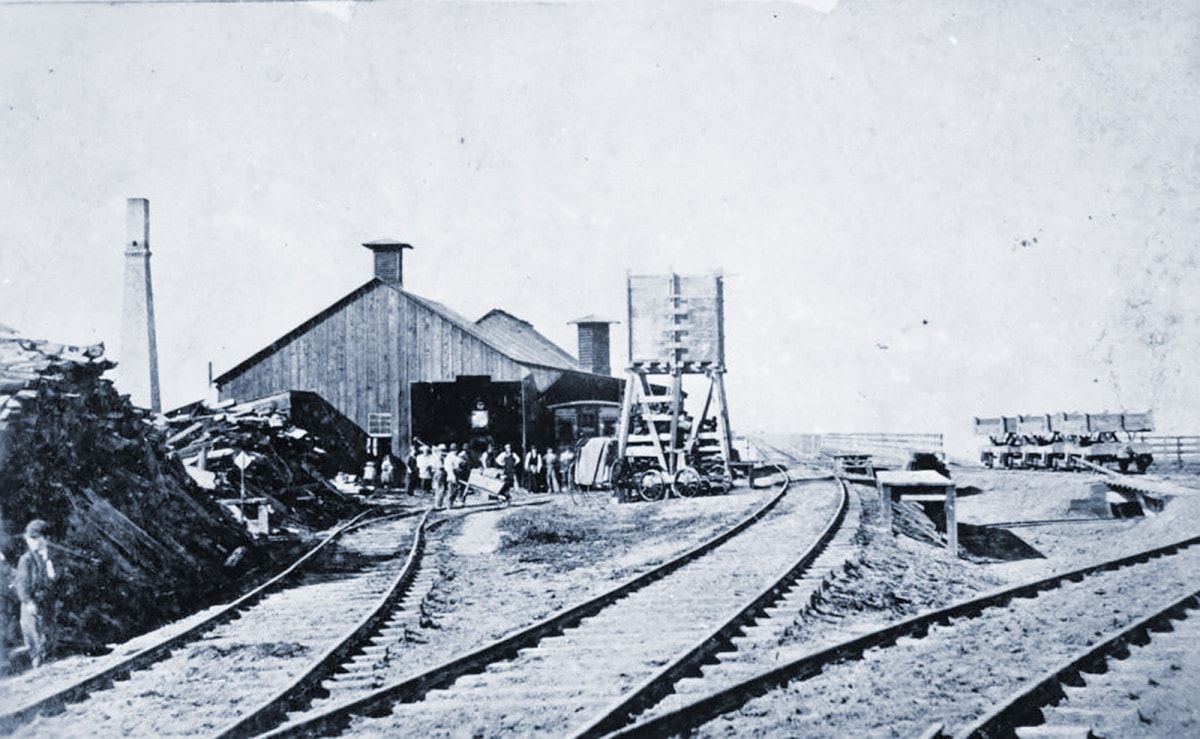

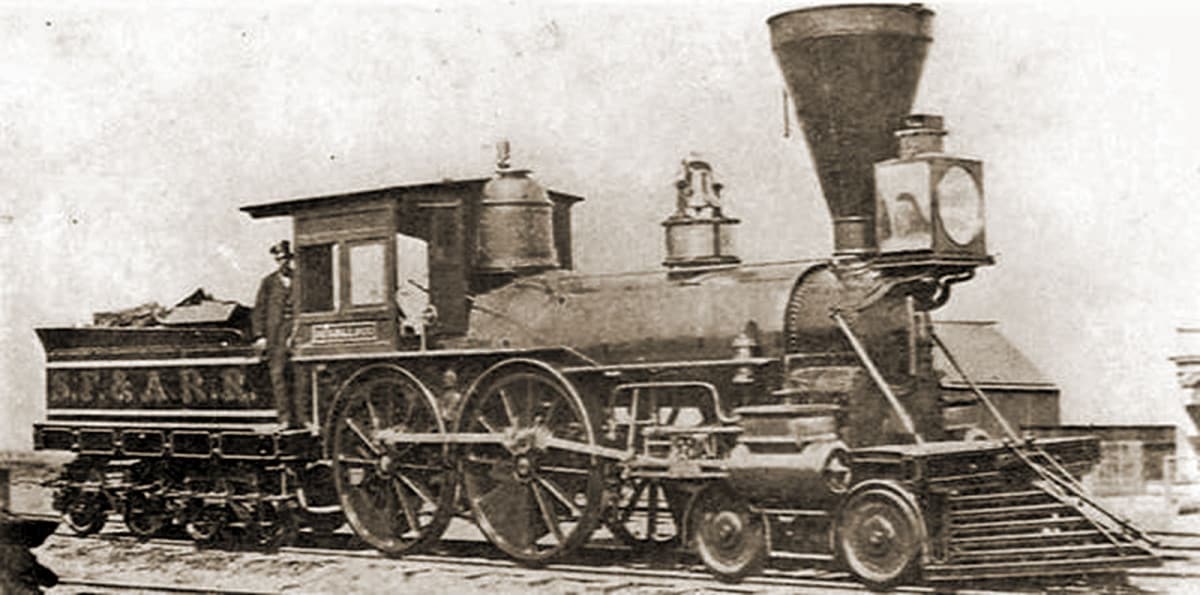

Cohen had built the railroad — the San Francisco & Alameda — that carried the Sept. 6 train to its destination, a pier at the foot of today’s Pacific Avenue. The train rolled out over the waters of San Francisco Bay to meet the ferryboat Alameda, which carried Stanford, Cohen and their fellow passengers to San Francisco.

People waited with great anticipation for the train to arrive at its first stop in Alameda, the station at today’s Lincoln Avenue and Park Street. They drank the beer and ate the food. They waited some more. Finally, at 10 p.m., the train rolled in, some four hours late, on the San Francisco & Alameda Railroad’s tracks to the waiting ferryboat.

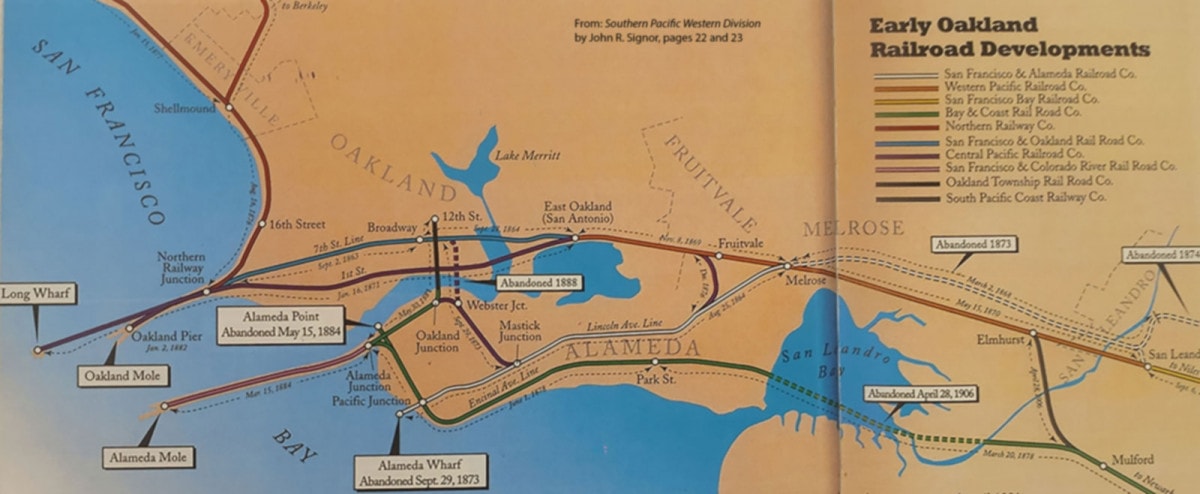

Cohen had also owned the San Francisco & Oakland Railroad. He acquired this line from his uncle Rodman Gibbons. Uncle Rodman had overextended himself trying to stretch his railroad from Seventh Street and Broadway in Oakland to today’s 14th Avenue near the former towns of Clinton and San Antonio. Gibbons hoped to cash in on the ferries that carried passengers to San Francisco from two wharves: one at the town of San Antonio, the other at the foot of Leviathan Street in the town of Encinal (Alameda’s Grand Street today.)

May Walking Tours: The Railroad Town of Alameda

Join Dennis for a two and one-half hour walking tour exploring Alameda’s role as a railroad town.

- This Saturday, May 28 — $15 A. A. Cohen brings the transcontinental railroad to town. We will meet by the corner of Pacific Avenue and Main Street on the West End. Get tickets now!

Space is limited, sign up now to guarantee your spot if you are interested in attending. Day-of-event tickets may be available for $20 per person, if space permits. Visit AlamedaPost.com/Tours for more information.

By Sept. 6, 1869, both the San Francisco & Alameda and San Francisco & Oakland railroads belonged to the Big Four. Cohen had sold them, along with their ferries and wharves to the Central Pacific Railroad. He received almost $300,000 in return, some $9 million translated to today’s spending power.

Both these railroads carried their passengers to the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay. The question arises: Why didn’t the Central Pacific Railroad simply run their trains into San Francisco? The answer lies deep in today’s Niles Canyon at a place called “Dead Cow Curve.” The truth in the story has all the markings of fiction, good fiction. As Lord Byron wrote in his 1823 poem, Don Juan:

“Tis strange, but true; for truth is always strange;

Stranger than fiction; if it could be told.”

In truth, the story why the Central Pacific Railroad trains never ran into San Francisco has failure and murder at its core, both stemming from the “Curse of Dead Cow Curve.” Alameda Creek shaped this curve — infamous to railroad buffs — in today’s Niles Canyon east of the railroad bridge at Farwell. The curve has a steep hill, and often cows grazing above Alameda Creek would lose their balance, fall into the ravine below and die.

Dead Cow Curve along Niles Canyon Road and Alameda Creek in Fremont, CA.

The men who built the successful San Francisco & San Jose Railroad in 1863 — Timothy Dame, Peter Donahue and Charles McLaughlin — decided to form the Western Pacific Railroad. They planned to use this company to build another iron road; this one to Sacramento. The project was a disaster. They and their crews worked to lay the first 20 miles of track. They wouldn’t see any money from the federal government until they completed the work.

They ran out of money while working. They reached Mile 20 at Dead Cow Curve. The government inspectors arrived in early October 1866 to certify the railroad’s work. They told Charles McLaughlin that he would get his money but not until the following January. There was paperwork, they explained. The Western Pacific was working on land that formerly (and may have still) belonged to the Spanish who had first laid claim to the real estate.

An angry McLaughlin walked off the job, leaving rails, ties, equipment, locomotives, and — most disturbing — his workers behind. One of the contractors, Jerome Cox, was expecting to receive $50,000, about $1.5 million in today’s money. McLaughlin could not pay Cox, and for the next 17 years, Cox took McLaughlin to court time and again. He lost every time. Cox accused his rival of paying off the judges. Cox had finally had enough.

On Dec. 14, 1883, Jerome Cox walked into McLaughlin’s office at 16 Montgomery St. in San Francisco, armed with a pistol. McLaughlin rose to greet his rival. Cox drew his weapon and shot McLaughlin dead.

“He asked me for $40,000. When I refused, he shot me,” McLaughlin said with his dying breath.

“It’s a lie,” Cox insisted. Many people knew of McLaughlin’s chicanery and sided with Cox. Cox never faced a jury. He was found “not guilty” at the coroner’s inquest.

In the meantime, the Central Pacific Railroad had built its wharves and, on Nov. 8, 1869, had begun running its trains into Oakland on two lines: passengers down Seventh Street and freight on First Street. The railroad got the rights to run its goods along the Oakland Estuary thanks to the flimflam of Horace and Edward Carpentier and their “Oakland Waterfront Company.”

The Big Four had more twaddle to lay on the table. They wanted to build wharves on Yerba Buena Island in a scheme rivals dubbed “The Goat Island Grab,” after the popular name for the pesky landmass the lay between Oakland and the railroad’s real goal: San Francisco.

The transcontinental railroad never reached San Francisco, despite what all its advertising promised. Did Jerome Cox place “The Curse of Dead Curve” on the Big Four? Or did Theodore Judah place the jinx on the railroad when the stagecoach and express company owners sent him away to Sacramento with his “crazy” plans for a railroad across the Sierra. Some even blame Jefferson Davis. He wanted the transcontinental railroad to run though the south.

More likely? There was no curse. It was simply a matter of who could talk the Big Four into the best way to reach the Pacific. For better or worse, Alameda won the prize as the transcontinental railroad’s first West Coast terminus. We have Cohen, his uncle Rodman, as well as the Carpentiers and all their shenanigans to thank for this. And we have much to celebrate.

The coming of this railroad changed Alameda’s fabric in ways that we no longer notice or remember.

The author would like to thank Alan Frank, curator of the Niles Canyon Railway, for his tales of Dead Cow Curve.

Dennis Evanosky is an award-winning East Bay historian and the Editor of the Alameda Post. His grandfather worked as a fireman tending the boilers on locomotives for the Erie Lackawanna Railroad in Pennsylvania. Dennis carried on the tradition, He once worked as Gandy dancer (a track-hand) for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in Maryland. Reach him at [email protected]. His writing is collected at AlamedaPost.com/Dennis-Evanosky.