In our previous articles exploring the history of Grand Station, we took a trip back in time to the resort era, when Louis Fassking created Alameda’s largest hotel and gardens [1], and saw how the end of that long period created a golden opportunity for the prolific homebuilder team Marcuse & Remmel.

[2]

[2]More stories emerge

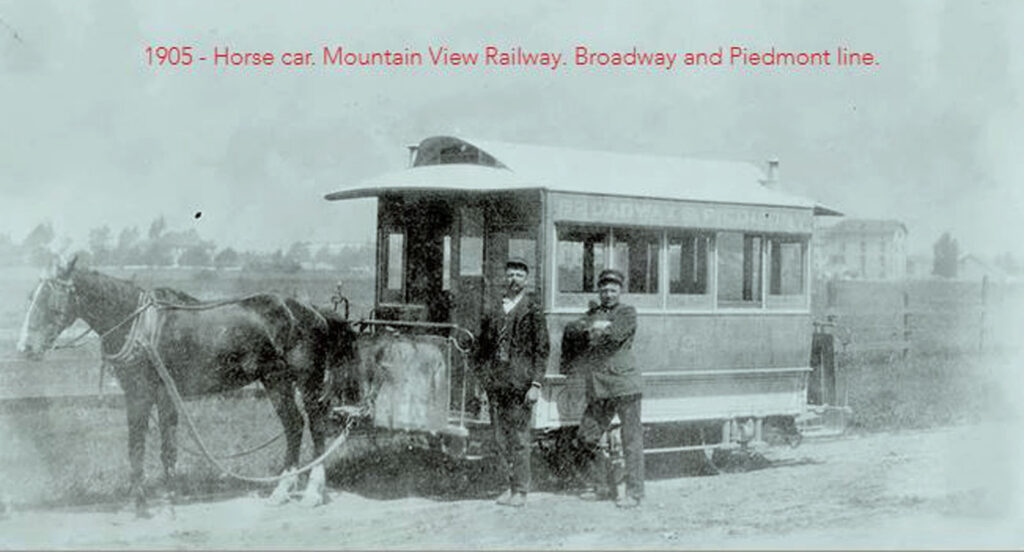

There are a few more stories associated with this period, and our exploration of this history wouldn’t be complete without touching on them. In Part 1 [1] of this series, we saw how the Alameda, Oakland, and Piedmont Railroad ran a horsecar line that made a stop at Fassking’s Station on Lincoln Avenue (then Railroad Avenue) near Grand Street. Louis Fassking was an early backer of the horsecar lines [4], and a car barn and stable were built on the Santa Clara Avenue side of his property. Directors of this railroad included Theodore Meetz, T. S. Fitch, and H. F. Shepardson. By 1878 they had five horsecars in operation. Fares were just 6¼ cents, and it took 40 minutes to travel from Broadway in Oakland, down Webster Street in Alameda, past Fassking’s Park on Railroad Avenue, and finally to Park Street.

A horsecar war

Trouble started brewing in 1878 when dissension arose in the ranks of the stockholders and directors of the company. Those associated with the businesses on Webster Street and the bathing resorts along Central Avenue wanted a branch line extended to the end of Webster. But Fassking and his supporters had no intention of losing his resort business to these competitors. At their annual meeting in December however, a new board of directors was elected, with T. W. Mead chosen as president and T. S. Fitch as superintendent. Meetz claimed that this election was illegal, and that management rightly belonged to the original directors. He put Louis Fassking in charge, and the war was on.

On December 13, 1878, a party led by Fitch overpowered Fassking and took over management. Headquarters was moved to a Webster Street saloon, which was fitted up as a waiting room and office, with a car barn and stable built alongside. Fares were reduced to 5 cents. The old directors went to court, and on January 9, 1879 they received an injunction preventing the new group from running the railroad. That same afternoon, the renegade group confiscated two of the cars and all service was halted. One of the cars was running south on Webster Street when Fitch appeared with Mead and lifted the car, passengers and all, off the track and ran it back to their stable. Two other cars were being held by Fassking, who had them run back to Edwin Forester’s Livery Stable in Oakland for safekeeping. The Fitch contingent sent an expeditionary force to Oakland and grabbed car number 5 out of Forester’s stable, and were able to begin service after a 24-hour suspension.

On January 13, Judge Wheeler directed Sheriff Jeremiah Tyrrel to put the old owners back in charge, and when the new owners resisted, they were cited for contempt. By the end of the month, Alameda’s horsecar war was over. Meetz, Fassking, and company were again running the railroad. Peace reigned once again in Alameda. During the following summer, fares went up to 10 cents, and the extension down Webster Street to the bathing beaches was built. The line was an immediate success, but while Fassking may have won the battle, he ultimately lost the war as his resort went out of business around 1880 [5]. The horsecar era eventually came to an end too, and by 1892 the horses were put out of work as all lines were electrified.

Under the cars

[6]

[6]Another story from the resort era at Grand Station involves a deadly accident at the station, an all too common occurrence at a time when heavy steam locomotives rolled down our streets. An article in the San Francisco Examiner, dated May 12, 1873, reported “The Shocking Death of Miss Hobson at Alameda.” The piece described how Miss Eliza Hobson (age not reported) had attended the Baptist picnic at Fassking’s Gardens on Saturday, May 10. At 4:10 p.m., while preparing to return home, she was crossing from the opposite side of the street as the train began to enter the station.

Suddenly startled by the sound of a carriage behind her, she attempted to jump over the track in front of the oncoming train but lost her balance, stumbled, and fell in front of the locomotive. Before she could even cry out, she was “whirled about and drawn under the moving train,” the report stated. “When the train was stopped, her body was found in a mangled condition beneath the fore-truck of the fifth car. Life was extinct.” Miss Hobson’s body was placed in a baggage car and brought to the wharf, where an inquest was held. She was then returned to San Francisco, where funeral services took place shortly thereafter.

This tragic story is a reminder of the dangers of having heavy rail operating on city streets. It also connects us to a previous story [7] about one of our Alameda Treasures, “The Fargo House” at 2242 San Antonio Ave., and how Miss Susie Diamond was also killed by a train in 1912, that time at Willow Station.

Another Marcuse & Remmel gem

[8]

[8]This final installment on Fassking’s Gardens also gives us an opportunity to marvel at another Marcuse & Remmel creation built on Minturn Court in 1892, on land formerly occupied by Fassking’s Hotel. 1528 Minturn Court is one of the better preserved/restored homes on the block, and showcases many of the signature elements used by Marcuse & Remmel in the early 1890s. From its Queen Anne High Basement style, to its incredibly rich decorated gable and bay window, and its inset full sunburst created in a woven ribbon texture, this home shouts Marcuse & Remmel to even the casual aficionado. The original cost of the cottage was $2,500, and the original owner was master mariner Elnathan Lewis, according to historian George Gunn. This home was once at least partially covered in stucco, so its current condition brings it back to something very close to its original look, and is something to celebrate.

A new discovery about an old mystery

[9]

[9]Another new discovery has come to light recently as a result of research for this article, thanks to Beth Sibley and Myrna van Lunteren. I had always wondered why 2031-2033 Eagle Ave. and 1909-1911 Stanford St.—buildings which were part of Fassking’s Hotel before being cut apart and moved—looked so different from each other in style. But this rare vintage photo shows what 2031 Eagle Ave. looked like before it was remodeled after moving from Fassking’s Park, and one can see how the two houses once looked more alike. Looking at the vintage photo of the Eagle Avenue house and the current day photo of the Stanford Street house, it is obvious that they are both Italianate style buildings from the early to mid-1870s. When imagining them joined together as part of Fassking’s Hotel, featuring all of their original architectural elements, and combined with the third wing (later demolished for lumber), one can begin to picture what the original Fassking’s Hotel looked like. After months of searching for an elusive image of the original hotel, this vintage photo may be our best clue yet.

And so our look into Fassking’s Gardens comes to a close, for now. I’ll keep looking for an image of the resort itself, and report back if I find one. The clues to the past may be elusive, but the things you find along the way turn the search into an adventure. From the coming of the railroads, to the age of the summer resort, to tragic fires and train accidents, to horsecar wars and new competition from bathing beaches, and to discoveries coming to light after 133 years, digging into the past is always filled with surprises. Join me next time as we continue looking into our Alameda Treasures.

For information on individual historic homes in Alameda, see George C. Gunn’s book, Documentation of Victorian and Post Victorian Residential and Commercial Buildings, City of Alameda 1854 to 1904, available at the Alameda Museum [10].

Source material about Alameda’s horsecar war is from the column “The Knave”, in The Oakland Tribune, July 15, 1973.

Contributing writer Steve Gorman has been a resident of Alameda since 2000, when he fell in love with the history and architecture of this unique town. Contact him via [email protected] [11]. His writing is collected at AlamedaPost.com/Steve-Gorman [12].