The Irish poet Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) once said, “Marriage is the triumph of imagination over intelligence. Second marriage is the triumph of hope over experience.” Though William Farragut Chipman’s first marriage to Sophie Koppitz ended in divorce in 1906 (see Part 1), by 1911 he had met Bernice Grace Harrell and was ready to take a second chance on love.

A small wedding and a honeymoon in the islands

The Alameda Daily Argus reported on June 27, 1911 that “William F. Chipman will claim Miss Bernice Harrell as his bride tonight. The ceremony will take place at the Hotel Bellevue in San Francisco at 8:30 o’clock, with only relatives present.” After the ceremony and a supper, the couple were to leave on an automobile tour, keeping their destination a secret. Next, they’d sail to the Hawaiian Islands for a few weeks of honeymooning, where they’d also visit with Chipman’s niece, Mrs. Florence Lansing and her husband Nelson.

After returning to California, the couple was to live in San Francisco, though there was a plan to build in Alameda in the future. As far as I can tell, though, other than maintaining a business address at his mother Caroline’s house at 1270 Weber St., the only residence information for William throughout the 1920s and 1930s is in San Francisco. William’s first house at 1290 Weber St. was either rented or sold to another occupant after his divorce from Sophie.

Alameda grows

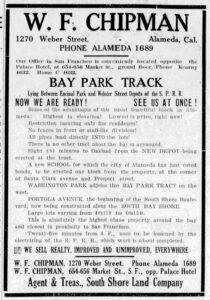

With the City of Alameda still growing, Chipman was busy selling real estate as an agent for the South Shore Land Company. In addition, his family still owned land in the Chipman East Tract, centered around Weber Street and San Antonio Avenue. He kept offices at both the Chipman family home at 1270 Weber St., and in San Francisco at 654 Market St.

Chipman’s ads in the Evening Times Star from this period offer lots for sale in the Bay Park tract, located “between Encinal Park and the Webster Street Depots of the Southern Pacific Railroad.” He offered large lots varying from 40 feet by 110 feet to 60 feet by 150 feet, on “the most beautiful blocks in Alameda.” This tract would have extended from around Verdi Street in the east, to Washington Park in the west. The existence of today’s Caroline Street, named for William’s mother Caroline Dwinelle (formerly Chipman), as well as streets named for her favorite composers—Weber, Mozart, and Verdi—are testaments to the Chipman family influence on Alameda in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

A new park, a dark street, and a rebellion in the ranks

During his life, William F. Chipman wasn’t shy about asking for what he wanted. In 1894, it was he who wrote to the Alameda City Council advocating for “a rockery and park, to be erected, with your consent and aid, at the junction of Central and Alameda avenues.” (See Today’s Alameda Treasure – The Rockery – Part 1.)

In 1907, a complaint to the city was filed by Weber Street property owners, signed by William F. Chipman, demanding arc or incandescent lighting on their street. “The street is still in darkness” claims the letter, despite a petition made to the Board of Trustees several weeks prior.

And in 1896, while William was serving as a captain in the California State Militia, a rebellion arose in the ranks. A story in the San Francisco Call, dated August 8, 1896, described how “over three months the war has been smoldering in Company G, breaking out at times into almost open rebellion.” The majority of the company claimed that their captain (Chipman) “was incompetent, and refused to be appeased.” Various attempts at arbitration were made, but in the end the men described as “malcontents” were dismissed and assigned to Company A instead.

It was thought that the trouble was over, but then “a surprise was furnished by Captain Chipman tendering his resignation as commander of Company G.” He refused to reconsider his decision to quit, and said only that he would have done so sooner but did not wish to resign under fire.

Death comes to a pioneer family

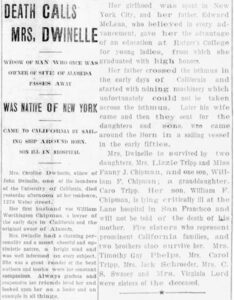

On April 16, 1912, Caroline Dwinelle, mother of William F. Chipman and his four siblings, died at the age of 80 in her home at 1270 Weber St. Newspaper articles described her as having grown up in New York City and being educated at Rutgers College. The young Caroline Elizabeth McLean, along with her mother and siblings, followed their father Edward McLean to California in the early 1850s, where he was seeking his fortune in mining. Mrs. Dwinelle was described as having had “a most charming personality and a most cheerful and optimistic nature, a bright mind and was well informed on every subject.” She was also remembered as being the widow of one of the founders of Alameda, William W. Chipman, and of one of the founders of the University of California, John W. Dwinelle.

An additional sad note to this story is that William F. Chipman was critically ill at a hospital in San Francisco when his mother died. So ill, in fact, that he wasn’t even told of her death until later. What that critical illness was we do not know. But he did go on to recover and live decades longer.

Up next

As we continue to explore the history of 1290 Weber St. and its connection to the Chipmans, we’ll learn about a little known chapter of Alameda’s history. This story, described in the newspapers as a “giant land battle,” involves the granddaughter of William W. Chipman making a bold claim of ownership on all of the new landfill acreage of South Shore, based on legal documents dating all the way back to the days of the Spanish Dons. How this epic battle plays out, along with the death of William Farragut Chipman, and how the Hodges family preserves the legacy of 1290 Weber St. to this day, will be the subject of our next installment.

Contributing writer Steve Gorman has been a resident of Alameda since 2000, when he fell in love with the history and architecture of this unique town. Contact him via [email protected]. His writing is collected at AlamedaPost.com/Steve-Gorman.